(almost) everything I read in 2024

or: my running list of excuses for why I didn't read as much as I wanted to

I was sick the week before Christmas, when I started writing this. Fever, chills, body aches, congestion, a bad cough—the classics. I’ve barely read a word since. I tried but illness made me too stupid. Instead, I catatonically watched Mad Men for hours upon hours, let it play in the background while I dozed off on the couch. At first I felt guilty about this—I have a research plan I need to stick to—but then I remembered rest is a luxury, even and especially when you’re on day 3 of a 101-degree fever.

Reading, too, can be a luxury, but this year it was something I did more for work than for pleasure. I enjoyed it regardless—I had fun!—but that wasn’t my primary motivation. Of the 34 books I read this year, just 6 were novels. I usually read a lot more fiction, but this was a somewhat unusual year.1

When 2024 began I was nannying in Williamsburg and working on my book proposal and working as a part-time paralegal and freelancing. It was a little chaotic but I loved it. I started nannying in late 2022, right after Thanksgiving: three days a week, five to six hours a day. It consumed me in a way no other job has—with children you always have to be on. At parties when people asked me how things were going I’d talk about the kids in the way other people talk about their bosses. And then one day in January I got either laid off or fired, I’m still not sure; they told me they wanted someone who would work full time, paid me for the next two weeks, asked if I’d be interested in occasional weekend babysitting. Later that week, or maybe the week after, they texted me to ask if I was free to watch the kids on a Saturday, but I wasn’t. I haven’t seen the kids since.2

The funny thing is I got fired and/or laid off from my nannying gig the day I was going to quit. I had been offered a job at a website covering someone’s maternity leave; the job started in March, I was going to give a month’s notice. Instead I spent February unemployed. My reading habits early in the year reflect this aimlessness: in late December and early January I read Tender Is the Night, which my boyfriend got me for Christmas, and Jonathan Blitzer’s fantastic Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here, which I reviewed for The Nation. At some point in February I got invited to a Middlemarch book club but I joined late and missed the second meeting because I was in Florida with Charlie, who was meeting my parents for the first time.3 We went to the beach and ate Publix sandwiches and I showed him around Tampa and one night he and my dad drank an entire bottle of Macallan together while we played a board game. At no point did I pick up Middlemarch, which I accidentally left in my childhood bedroom. Charlie lent me his copy when we got back to New York but no matter how much I read I was constantly behind the rest of the group; I didn’t go to a single meeting and put it down for good sometime in mid-March, shortly after starting my new job.

Nannying was more physically demanding than typing on a laptop, and more emotionally demanding too. I pushed a stroller all around Williamsburg, carried an unusually tall toddler in my arms when he asked to be picked up. I played hide and seek and ran around McCarren pretending to be an evil witch who eats children. Sometimes I’d be annoyed or frustrated but I was never allowed to show it. I was always, always speaking at a level a four-year-old could understand, which meant I was often thinking at a level a four-year-old could understand. At the end of the day, I wanted adult conversation; I wanted literature.

Then suddenly I was at a computer and I was reading and writing all day and the idea of doing additional reading and writing in my spare time no longer felt like leisure. I still had freelance assignments to wrap up and a book proposal to finish. In late March I re-read Greg Grandin’s The End of the Myth for research; in April, while visiting Charlie’s family in Minnesota, I read César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández Welcome the Wretched and Ana Raquel Minian’s In the Shadow of Liberty, both of which I planned on reviewing. When I got back to New York I sat down to write the piece and the words wouldn’t come out. I rarely experience writer’s block; mostly I think it’s fake. But this time I just couldn’t do it. Around the same time, I reviewed two books about refugee and migrant women—Kimberly Meyer’s Accidental Sisters and Susan J. Terrio’s Forced Out—for the Los Angeles Review of Books.

After that I didn’t read for pleasure at all until late May, when I went to Spain and Italy with my family. I had a lot of excuses, all of them bad: I was busy with work, I was burnt out, I was moving into a new apartment, I was stressed. In hindsight this makes me unbelievably sad. Reading was something I loved and suddenly it wasn’t. To change this, and because I believe in light, thematic vacation reading, I packed My Brilliant Friend, a sort of companion to my family trip to Ischia,4 which the narrator visits in the first novel. I read it in the thermal baths and finished it on the ferry back to Naples. The next day before my flight to Madrid, went to the airport bookstore assuming they’d have The Story of a New Name, the second installment in Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet.5 They didn’t have it, at least not in English, so I picked up Susan Sontag’s The Volcano Lover instead. I breezed through it during the last few days of my vacation and on the flight home. It felt good to read again, to actually be engrossed in something.

Then I got back to New York and once again found myself unable to read anything longer than a feature. I told myself this was temporary: I had moved my things into my new apartment two days before going on vacation, I had to unpack, I had to work, I had some personal turmoil, I had to finish my book proposal. I went to the Minnesota state fair with Charlie; I went to Idaho to visit Alina’s family and then I went to LA to visit Eliza, who is getting married next year. We got brunch and hiked around Griffith and went to bridal shops where I took photos of her as she tried on dresses. I took The Member of the Wedding with me, which was sweet and poignant; the narrator’s pre-adolescent aimlessness reminded me of my own, both then and now. But I accidentally left the book at Eliza’s; she shipped it to me a few months later along with some ceramics she’d made me that didn’t fit in my bag, but by then I had moved on.

Sometime in late August the used bookstore near me had a copy of The Story of a New Name, which I read on a brief trip to San Francisco where I stayed with Alina, a brilliant lawyer. I read it in her bed as she worked into the night.6 A few weeks later she came to New York for my birthday and told me she wanted to read My Brilliant Friend before her trip to Sicily. I lent her the second Neapolitan novel while I read the third, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay; we texted incessantly about the characters, about friendship, about trying to escape your origins and turning into your parents anyway. I finished the final novel in the series, The Story of the Lost Child, in a hammock in my parents’ backyard in the humid days between hurricanes Milton and Helene. They were in Croatia; I was house-sitting. Alina and I made a pact to read Domenico Starnone’s The House On Via Gemito together, which I enjoyed more than she did. I was about a third of the way through when I decided I needed to get serious about research for my book; I had obviously done some while writing my proposal, but it no longer felt sufficient.

I think being in Florida is what fixed me. I had to wake up early every morning to take my brother to school. Most of my friends here have since moved away, so I had very few distractions, very little to do besides walk around the neighborhood and look at the sandhill cranes. Rereading my proposal, I found myself with unanswered questions, mostly about the history of the frontier before the events in my book began. I decided to get serious about reading: to treat it like a job, and in doing so, hopefully retrain my attention span. Thanks to my NYU degree (a phrase I doubt is used often with sincerity, and yet here I am) I have unlimited access to certain academic databases, including Jstor and Project MUSE, which I used to download books and articles that seemed related to what I was writing about, even if obliquely. I read one print book and one ebook at a time, each for an hour a day after work. The list, in order, is as follows:

I won’t go into detail about each of these; some were useful and some weren’t. Some were well written and some weren’t. Almost all were interesting to some degree or another. (My favorites: Wild by Nature; Epiphany in the Wilderness; Dispossessing the Wilderness; Vanishing America; Making the White Man’s West.) What matters more to me is the way I read—the articles and reviews interspersed between books, which aren’t represented here; the way the authors were in conversation with each other;7 the joy of checking a citation and finding something I’d already read, or even better, something new to read. I started reading everywhere: on the train, on the treadmill, at home before and after work, on flights (I went to Tampa in October and Detroit in November), instead of going out.

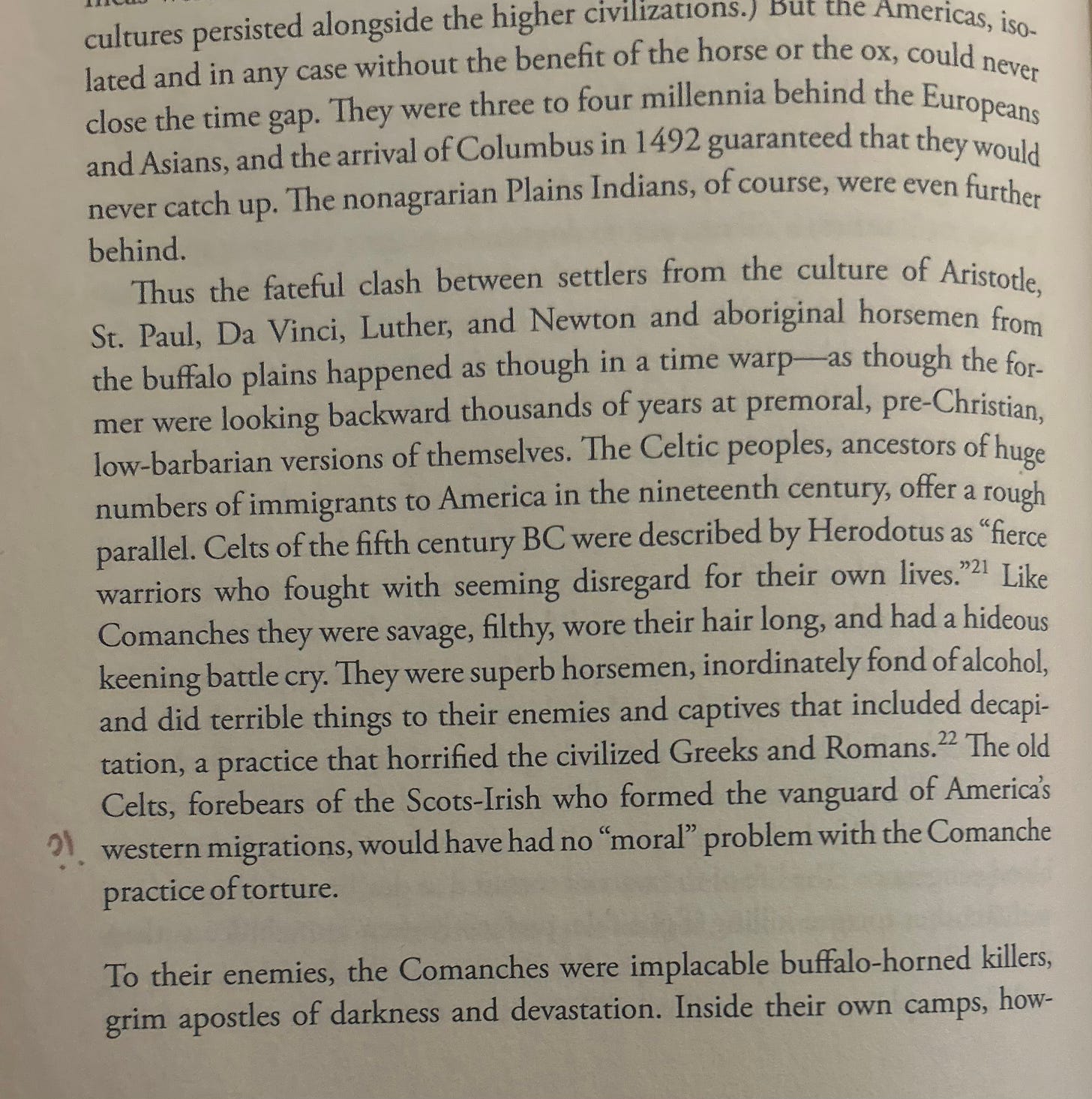

Though I was enthralled—one night while reading Making the White Man’s West I kept pausing to tell Charlie a new, interesting thing I had learned, some of which he didn’t find nearly as interesting as I did—a lot of these books were dry. Only one, S.C. Gwynne’s Empire of the Summer Moon, which I remember buying at a Half Price Books while visiting Rachel in Austin, was character-driven enough to read like a novel; the rest were rigorous, academic. But Gwynne’s book, despite its generally good pacing, was stunningly racist; I was shocked to learn it was published in 2010, just two years after Pekka Hämäläinen’s Comanche Empire, which won the Bancroft Prize. Gwynne doesn’t cite Hämäläinen once; I suppose he could have written the manuscript before Comanche Empire was released, but it still feels like an oversight. Instead, he relies almost entirely on accounts from Texas Rangers, white settlers, and people who were kidnapped by the Comanche, and so the book reads like this:

Around this time I got so absorbed in my research I refused to do much of anything else. One night, as a “break,” I proposed that Charlie and I watch Deadwood since it was somewhat thematically relevant. After September I didn’t read a single novel. I tried reading Via Gemito but was no longer interested in the postwar life of a Neapolitan painter and his son. Looking back, I miss novels—I miss reading for pleasure. I brought Via Gemito to Florida with me and have been reading it on and off, trying to regain the attention span I lost during a week and a half of illness when all I did was watch Mad Men and play Stardew Valley. It’s working, mostly, though it feels shameful to admit that a two-week period of illness was all it took to turn my brain into rice pudding. Allison (black hair, not red hair) told me iPad baby brain is temporary, I just have to be careful.

Next year I’d like to read fiction again, though I already know I’ll find myself bored by anything that isn’t at least tangentially related to my research. I’ve made a short list of novels that I plan on reading alongside my massive pile (literal and proverbial, since about half are ebooks) of research texts: Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon,8 Ella Deloria’s Waterlily, John Williams’ Butcher’s Crossing. I’m going to read a lot of Willa Cather and Edith Wharton and Henry James and maybe some Fitzgerald; I’m going to reread Blood Meridian and finally pick up Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. But first I’m going to finish Via Gemito, which I’ve neglected for far too long.

To compare: I read 41 books in 2023, a little over half of which were novels or short story collections.

A magazine editor asked me to write about the experience but I declined. It’s too personal, too hard to do without turning other people’s lives, including that of a small child, into “content.”

We hastily planned the trip after we signed a lease together, since we figured my parents should at least meet the man I was going to live with. He stayed in an Airbnb because my mom wouldn’t let us sleep in the same bed under her roof. Now that we live together, though, apparently it’s fine.

Ischia rules btw

I originally read My Brilliant Friend in 2021 during an earlier family trip to Italy. We visited Rome and Naples. When I got back to New York I borrowed The Story of a New Name from a guy I was seeing at the time. I picked it up from his place the day after I got back; I was on my way to the airport again, this time on a reporting trip to Arizona, where I spent 48 hours with Customs and Border Protection for a story on border surveillance technology for The Verge. I bought the third book, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, at a Tucson Barnes & Noble right before closing, and the fourth, The Story of the Lost Child, at a used bookstore in Ajo, a tiny town right on the border, for $2.50. The following year I lent the second Neapolitan novel to a very sweet guy I was seeing (a different one; the guy at the beginning of this footnote was a dud) and never got it back after things fizzled out. A month or so ago I ran into him outside his apartment and he gave it back; after starting the series, he decided he’d rather read it in the original Italian.

This has been our dynamic since freshman year of college, when we were randomly assigned roommates, though back then I was mostly partying and she was mostly studying.

I picked up Duval’s Native Nations after reading some critical reviews of Hämäläinen, some of which I agreed with, others which I didn’t. Duval’s was more of a social history, while Hämäläinen focused more on diplomacy and military conflict; it was nice to read the two so closely together.

Charlie and I each have a copy and we’re going to read it together <3

That book quote...arrrggh.

I've read extensively on the Nez Perce war, and the conclusion I came to very quickly was that one generation's difference in white settlement would have resulted in a *very* different look for western US colonialism. Or if John McLoughlin could have convinced settlers, trappers, and Natives alike to form a country independent from Great Britain and the US. Lots of possible turning points.