A little over four years ago, I quit my job to go freelance. It was a scary and maybe foolish decision, at least from a financial standpoint, but it was also the most professionally fulfilling thing I’ve ever done. One of my friends recently made fun of me for tweeting something along the lines of “writing is so fun I can’t believe this is my job” every three months or so, but it is so fun and I genuinely feel so lucky to get to think and read and write for a living, and I feel even luckier that people read and seem to enjoy my work.

One of my goals this year was to write book review, and thanks to Jess Bergman, my amazing editor at The Baffler, I did so more than once. I reviewed The Slow Violence of Immigration Court by Maya Pagni Barak and Suspended Lives by Bridget M. Haas for their spring issue, in a sort of sprawling essay about the structural violence of the immigration system. I also reviewed Alejandra Oliva’s stunning memoir Rivermouth, about her time translating for asylum seekers at the border and in New York City, which I cannot recommend enough. I also wrote about the surveillance technologies that link Israel’s apartheid regime and our border surveillance apparatus; Democrats’ hypocrisy on asylum seekers for The Nation; and migrants who were living in a vacant office building for Curbed. And I finally got to write about a longtime obsession of mine—crunchy, back-to-the-land reactionaries—not once but twice. For the latest issue of The Drift, I analyzed the specter of left-wing eco-terrorism and the actual threat of right-wing eco-fascism. And for The Baffler, I wrote the feminine analogue to the men who kill people of color in the name of the environment: tradwives.

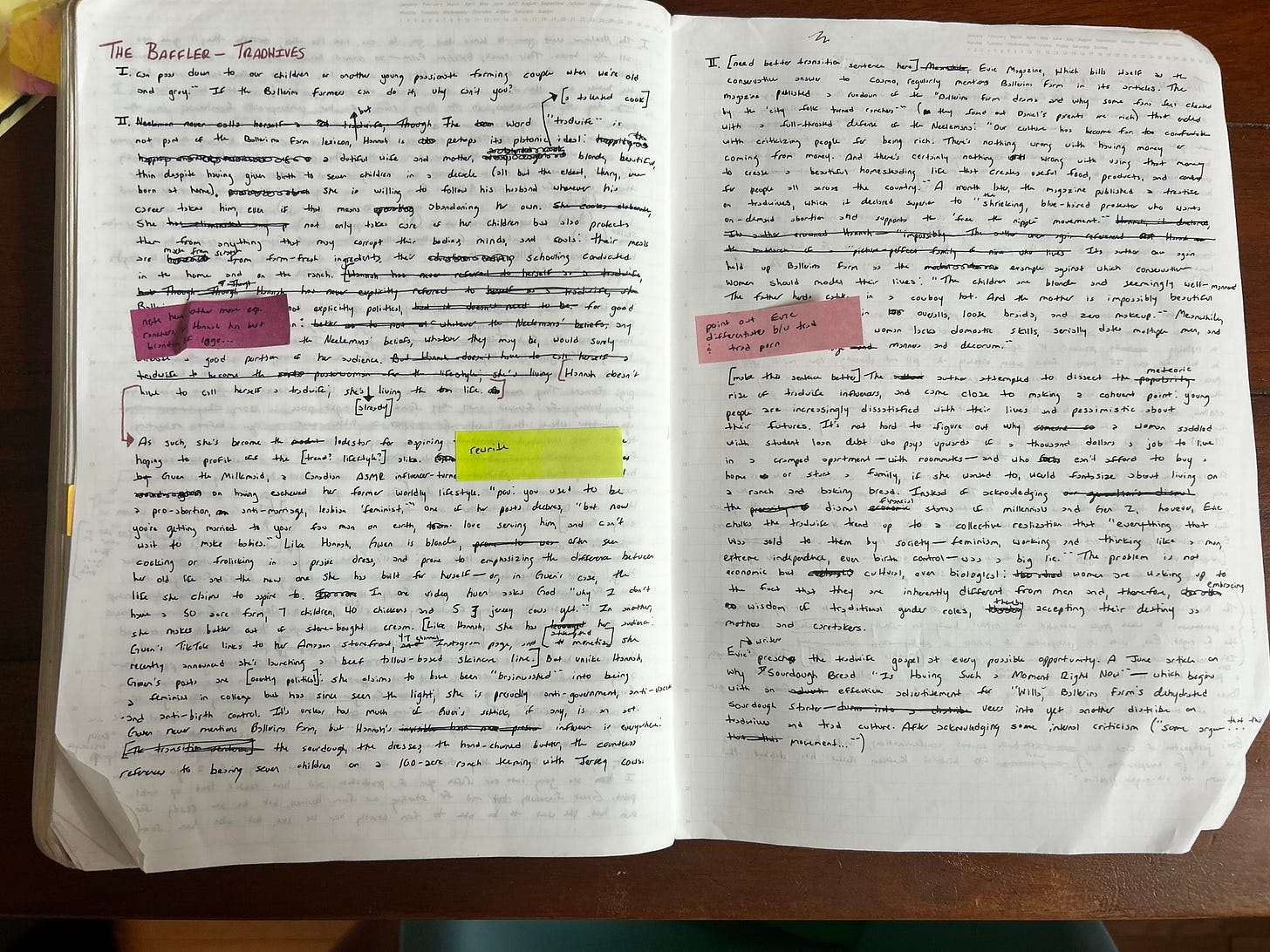

All told, I published less than a dozen pieces this year, which was still more than I expected. (And which took a really long time, since I write all my first drafts by hand, which I swear by even though it freaks people out.) When I quit my staff job in 2019, I did so with the goal of slowing down, spending weeks or months on a single draft instead of days—or, more likely, a few hours.

Which brings me to the point of this post, and of this newsletter in general. Self-promotion is an embarrassing but undeniably important part of this job. But in addition to a year-end roundup of my work, I wanted to talk a bit about the research that went into it. I spend most of my time reading, not writing, which I’ve come to think is the most important part of the whole process. And most of what I read doesn’t make it into my final drafts, though it always informs them.

I read Jhumpa Lahiri’s Translating Myself and Others in conjunction with Rivermouth, because while I know a fair amount about the border and the asylum system, I don’t know much about the art of translation. I’ve interpreted a lot for my own work, and have spent a lot of time thinking about the best way to convey someone else’s words in a different language, but I haven’t thought much about written translation, which Oliva writes about deftly.

For my tradwives piece, I reread Prairie Fires by Caroline Fraser, a fascinating biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, the original tradwife influencer, and Conceiving the Future by Laura Lovett, one of my favorite nonfiction books of all time, which is where I first learned about eugenic baby contests. I downloaded way too many Jstor articles about homesteading and didn’t read most of them, but I did read “women's diaries on the western frontier” by lillian schlissel, which was published in the spring 1977 edition of the American Studies journal.

And for my Drift essay on eco-fascists and eco-terrorists, I obviously watched How To Blow Up a Pipeline, which I didn’t love—I found it too didactic, because literally teaches you how to blow up a pipeline (it doesn’t) but because its politics are clumsily written into the script. I read The Ecocentrists by Keith Makoto Woodhouse and Green Is the New Red by Will Potter, both of which recount the history of real environmental radicals—and, in the case of The Ecocentrists, into the sometimes incongruent politics of the radical environmentalist movement of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Kathleen Belew’s Bring the War Home helped me contextualize how the federal government cared more about the mostly made-up threat of eco-terrorism than the real threat of white nationalism in the years following the Vietnam War and beyond, and Blood Red Lines, by my friend Brendan O’Connor, goes deep into the ties between immigration restriction groups and white supremacists.

I tried to keep this little retrospective brief, but in future editions of this newsletter (which I promise will be infrequent and irregular), I’ll probably include interesting excerpts from what I’ve been reading, snippets of things that didn’t make it into my drafts, etc. That’s all for now.

xoxo and happy new year <3